By C. Avogadro. Baylor College of Dentistry. 2018.

Outbreaks such as poliomyeli- tis may leave in their wake patients with an immediate need for physio- therapy and rehabilitation; timely organization of these services will lessen the impact of the outbreak buy 2 mg ginette-35 amex. Implement control measures to prevent spread After the epidemiological characteristics of the outbreak have been better understood ginette-35 2 mg mastercard, it is possible to implement control measures to prevent further spread of the infectious agent buy generic ginette-35 2 mg online. However, from the very beginning xxx of the investigation the investigative team must attempt to limit the spread and the occurrence of new cases. Immediate isolation of affected persons can prevent spread, and measures to prevent movement in or out of the affected area may be considered. Whatever the urgency of the control measures they must also be explained to the community at risk. Population willingness to report new cases, attend vaccination campaigns, improve standards of hygiene or other such activities is critical for successful containment. If supplies of vaccine or drugs are limited, it may be necessary to identify the groups at highest risk initial for control measures. Once these urgent measures have been put in place, it is necessary to initiate more perma- nent ones such as health education, improved water supply, vector control or improved food hygiene. It may be necessary to develop and implement long-term plans for continued vaccination after an initial campaign. Conduct ongoing disease surveillance During the acute phase of an outbreak it may be necessary to keep persons at risk (e. After the outbreak has initially been controlled, continued community surveillance may be needed in order to identify addi- tional cases and to complete containment. Sources of information for surveillance include: i) notifications of illness by health workers, community chiefs, employers, school teachers, heads of families; ii) certification of deaths by medical authorities; iii) data from other sources such as public health laboratories, entomological and veterinary services. It may be necessary to maintain estimates of the immune status of the population when immunization is part of control activities, by relating the amount of vaccine used to the estimated number of persons at risk, including newborns. Prepare a report A report should be prepared at intervals during containment if possible, and after the outbreak has been fully contained. Reports may be: i) a popular account for the general public so that they understand the nature of the outbreak and what is required of them to prevent spread or recurrence; ii) an account for planners in the Ministry of Health/local authority so as to ensure that the necessary administrative steps are taken to prevent recurrence: iii) a scientific report for publication in a medical journal or epidermiological bulletin (reports of recent outbreaks are valuable aids when teaching staff about outbreak control). For example, it may be necessary to show that sliced foodstuffs can be contaminated by an infected slicing machine if this has not been proven during the outbreak investigation. Such verification requires more laboratory facilities than are available in the field, and is often not completed until long after the outbreak has been contained. The response will of necessity involve the intelligence com- munity and law enforcement agencies as well as public health services, and possibly the Defence Ministry as well, especially if the event is considered of non-domestic origin. Difficulties in communication and approaches may arise, since these disciplines do not usually work to- gether. The public health response included identifying all those at risk of infection through the postal system, and prescribing antibiotics to over 32 000 persons identified as potentially in contact with envelopes contaminated with anthrax spores. The event and associated hoaxes caused unprecedented demands on public health laboratory services, and several nations had to recruit private laboratories to deal with the overflow. If the agent is widely dispersed and/or easily transmissible, a surge capacity may be required to accommodate large numbers of patients, and systems must be available for the rapid mobilization and distribution of medicines or vaccines according to the agent released. In the event that the agent is transmissible, additional capacity will be required for contact tracing and active surveillance. Some of the infectious agents of concern include bacteria and rickettsia (anthrax, brucellosis, melioidosis, plague, Q fever, tularemia, and typhus), fungi (coccidioidomycosis) and viruses (arboviruses, filoviruses and variola virus). International threat analysis xxxii considers that deliberate use of biological agents to cause harm is a real threat and that it can occur at any time; however, such risk analysis is not generally considered a public health function. According to national intelligence and defence services, there is evi- dence that national and international networks have engineered biological agents for use as weapons, in some instances with suggestions of attempts to increase pathogenicity and to develop delivery mechanisms for their deliberate use. Infection of humans may be a one-time occurrence, or may be repeated over a period of time after the initial occurrence. The agent used will determine whether there is a risk of person-to-person transmis- sion after the initial and subsequent attacks; information on this risk is covered in more detail under specific disease agents. Incubation period, period of communicability and susceptibility are agent-specific. Prevention of the deliberate use of biological agents presupposes accurate and up-to-date intelligence about terrorists and their activities. The agents may be manufactured using equipment necessary for the routine manufacture of drugs and vaccines, and the possibility of dual use of these facilities adds to the complexity of prevention. This has led some analysts to regard a strong public health infrastructure, with rapid and effective detection and response mechanisms for naturally occurring infectious diseases of outbreak potential, as the only reasonable means of responding to the threat of deliberately caused outbreaks of infectious disease. Adequate background information on the natural behaviour of infectious diseases will facilitate recognition of an unusual event and help determine whether suspicions of a deliberate use should be investigated. Preparedness for deliberate use also requires mechanisms that can be immediately called into action to enhance communication and collabora- tion among the public health authorities, the intelligence community, law enforcement agencies and national defence systems as need may arise. Preparedness should draw on existing plans for responding to large-scale natural disasters, such as earthquakes or industrial or transportation accidents, in which health care facilities are required to deal with a surge of casualties and emergency admissions. Most health workers will have little or no experience in managing illness arising from several of the potential infectious agents; training in clinical recognition and initial management may therefore be needed for first xxxiii responders. This training should include methods for infection control, safe handling of diagnostic specimens and body fluids, and decontamina- tion procedures. One of the most difficult issues for the public health system is to decide whether preparedness should include stockpiling of drugs, vaccines and equipment. Outbreaks of international impor- tance, whether naturally occurring or thought to have been deliberately caused, should be reported electronically by national governments to outbreak@who. They may then be free of clinical signs or symptoms for months or years before other clinical manifestations develop. A single test is recommended in populations with a prevalence rate above 10%; lower prevalence levels require a minimum of 2 different tests for reliability.

In 2001 2mg ginette-35 mastercard, an estimated 282 000 people worldwide died of tetanus generic ginette-35 2 mg with mastercard, most of them in Asia purchase ginette-35 2mg online, Africa and South America. In rural and tropical areas people are especially at risk, and tetanus neonatorum is common (see below). There is some inconclu- sive evidence that at high altitude the risk for tetanus could be lower. Reservoir—Intestines of horses and other animals, including hu- mans, in which the organism is a harmless normal inhabitant. Tetanus spores, ubiquitous in the environment, can contaminate wounds of all types. Mode of transmission—Tetanus spores are usually introduced into the body through a puncture wound contaminated with soil, street dust or animal or human feces; through lacerations, burns and trivial or unnoticed wounds; or by injected contaminated drugs (e. Tetanus occasionally follows surgical procedures, which include circumcision and abortions performed under unhygienic conditions. The presence of necrotic tissue and/or foreign bodies favors growth of the anaerobic pathogen. Incubation period—Usually 3–21 days, although it may range from 1 day to several months, depending on the character, extent and location of the wound; average 10 days. In general, shorter incubation periods are associated with more heavily contaminated wounds, more severe disease and a worse prognosis. Infants of actively immunized mothers acquire passive immunity that protects them from neonatal tetanus. Recovery from tetanus may not result in immunity; second attacks can occur and primary immunization is indicated after recovery. Preventive measures: 1) Educate the public on the necessity for complete immuniza- tion with tetanus toxoid, the hazards of puncture wounds and closed injuries that are particularly liable to be compli- cated by tetanus, and the potential need after injury for active and/or passive prophylaxis. In countries with incomplete immunization programs for children, all pregnant women should receive 2 doses of tetanus toxoid in the first pregnancy, with an interval of at least 1 month, and with the second dose at least 2 weeks prior to childbirth. Nonadsorbed (“plain”) preparations are less immunogenic for primary immunization or booster shots. Vaccine-induced maternal immunity is important in preventing maternal and neonatal tetanus. For major and/or contaminated wounds, a single booster injection of teta- nus toxoid (preferably Td) should be administered promptly on the day of injury if the patient has not received tetanus toxoid within the preceding 5 years. When antitoxin of animal origin is given, it is essential to avoid anaphylaxis by first injecting 0. Pretest with a 1:1000 dilu- tion if there has been prior animal serum exposure, together with a similar injection of physiologic saline as a negative control. If after 15–20 minutes there is a wheal with surrounding erythema at least 3 mm larger than the negative control, it is necessary to desensitize the individual. Control of patient, contacts and the immediate environment: 1) Report to local health authority: Case report required in most countries, Class 2 (see Reporting). Metronidazole, the most appropriate antibiotic in terms of recovery time and case-fatality, should be given for 7–14 days in large doses; this also allows for a reduction in the amount of muscle relaxants and sedatives required. Maintain an adequate airway and employ sedation as indicated; muscle relaxant drugs together with tracheostomy or nasotracheal intubation and mechanically assisted respiration may be lifesaving. Epidemic measures: In the rare outbreak, search for contam- inated street drugs or other common-use injections. International measures: Up-to-date immunization against tet- anus is advised for international travellers. In the past 10 years the incidence of tetanus neonatorum has declined considerably in many developing countries thanks to improved training of birth attendants and to immunization with tetanus toxoid for women of childbearing age. Most newborn infants with tetanus have been born to nonimmunized mothers delivered by an untrained birth attendant outside a hospital. The disease usually occurs through introduction via the umbilical cord of tetanus spores during delivery through the use of an unclean instrument to cut the cord, or after delivery by ‘dressing’ the umbilical stump with substances heavily contaminated with tetanus spores, frequently as part of natal rituals. Tetanus neonatorum is typified by a newborn infant who sucks and cries well for the first few days after birth but subsequently develops progres- sive difficulty and then inability to feed because of trismus, generalized stiffness with spasms or convulsions and opisthotonos. Overall, case-fatality rates for neonatal tetanus are very high, exceeding 80% among cases with short incubation periods. Neurological sequelae including mild retardation occur in 5% to over 20% of those children who survive. Prevention of tetanus neonatorum can be achieved through a combina- tion of 2 approaches: a) improving maternity care with emphasis on increasing the tetanus toxoid immunization coverage of women of child- bearing age (especially pregnant women), and b) increasing the propor- tion of deliveries attended by trained attendants. Important control measures include licensing of midwives; providing professional supervision and education as to methods, equipment and techniques of asepsis in childbirth; and educating mothers, relatives and attendants in the practice of strict asepsis of the umbilical stump of newborn infants. The latter is especially important in many areas where strips of bamboo are used to sever the umbilical cord or where ashes, cow dung poultices or other contaminated substances are traditionally applied to the umbilicus. In those areas, any woman of childbearing age visiting a health facility should be screened and offered immunization, no matter what the reason for the visit. Nonimmunized women should receive at least 2 doses of tetanus toxoid according to the following schedule: the first dose at initial contact or as early as possible during pregnancy, the second dose 4 weeks after the first and preferably at least 2 weeks before delivery. A third dose could be given 6–12 months after the second, or during the next pregnancy. A total of 5 doses protects the previously unimmunized woman through- out the entire childbearing period.

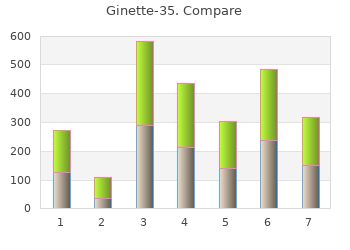

10 of 10 - Review by C. Avogadro

Votes: 33 votes

Total customer reviews: 33